Opinions

India’s Kashmir move: Two perspectives

Author - Baijayant ‘Jay’ Panda

Posted on - 11 September 2019

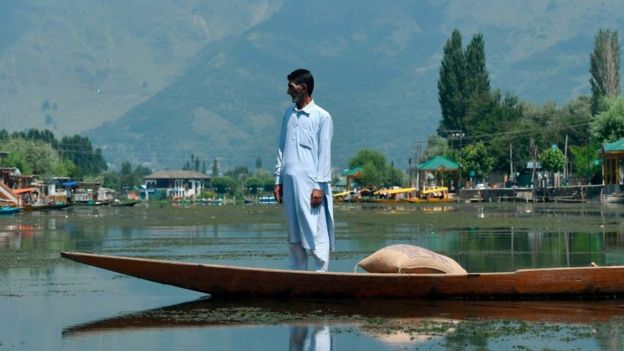

Image Source - Some of the biggest Indian companies have indicated they will announce large investments in the region | AFP

Downloadables

It’s notable that the government’s move on Kashmir has enthused many more Indians than just the BJP’s staunch supporters – many opposition leaders have also supported it.

There have, however, been bitter recriminations by Kashmiri separatists, as well as some in India’s opposition, who claim the move is unconstitutional and will end in tears.

But it is hard to predict how a defanged Article 370 could in practice be any worse than the decades during which it prevailed.

That era saw well over 40,000 deaths in Kashmir as well as two wars and a limited conflict fought over the region by India and Pakistan. It also saw the brutal persecution of hundreds of thousands of its minority Hindu Pandit community, who were forced out of the region in the 1990s as Muslim militancy grew.

The move to revoke Article 370 enthused many more Indians than just the BJP’s staunch supporters

Kashmir now has the potential to be infinitely better.

The region’s special status under Article 370 meant that many progressive Indian court rulings and laws passed by parliament did not apply there.

These included the prevention of child marriages, the rights of Dalits (formerly untouchables), attempts to eliminate discrimination against women and the LGBTQ community, and the prevention of corruption, among many others.

The Nehru government’s introduction of Article 370 into India’s constitution in 1949, granting the region its own constitution, flag, and special status, was never tenable in the long run. Even Nehru himself said so, and it was explicitly worded as a temporary provision.

In any event, Kashmir formally acceded to India in October 1947 under the same rules as all other princely states.

Thereafter, strictly speaking, both the introduction of Article 370 and its amendments were a matter for India’s Parliament. Neither Pakistan nor any other body has any legal role in the matter, any more than it would have for any other state that acceded to India.

Importantly, the people of the region continue to have the same democratic rights as before, just like citizens of any other part of India. They will still have elections and constitutional rights of equality, just like all of India’s 1.36 billion citizens, including more than 200 million Muslims.

And although, as a union territory, it will have less devolution of administrative powers from the federal government than states, it will allow the union government to better co-ordinate federal and state resources for security.

Kashmiri separatists, as well as some in India’s opposition, claim the move is unconstitutional and will end in tears

Since 1948, India’s huge infusion of federal funds into Jammu and Kashmir (four times the amount for the rest of the country on a per capita basis) has not had a proportionately lasting effect.

Though on several socioeconomic parameters Kashmir seems to be near the Indian average, that is not because of its own development, but rather because of large handouts from Delhi.

Its special provisions not only facilitated enormous leakages from the Indian treasury, in conjunction with the security situation it also inhibited investment in a sustainable local economy.

That is set to change dramatically. A major business meeting is planned for October, and some of the biggest Indian companies have indicated they will announce large investments. It is not just the big players – many others are keen to participate in its development.

Land is an emotive issue all over the Indian subcontinent and this region is no exception. Article 370 not only prevented Indians from other parts from buying land there, but even disenfranchised Kashmiri women who married non-Kashmiris. Modern, liberal democracies should have no place for such discrimination.

Though there are similar restrictions in a few other states as well, there is a crucial difference. In the northern state of Himachal Pradesh, for instance, there is a specified length of residency required before Indians from outside the state can buy land. While requiring a demonstration of commitment to a region for land purchase can arguably be a good thing, a total ban based on regionalism or gender will only foster ghettoisation.

Some of the biggest Indian companies have indicated they will announce large investments in the region

Similar arguments have been made about preserving the demographics of India’s only Muslim-majority state.

That goes to the root of Pakistan’s angst about the region because of its foundational two-nation theory – but that is surely redundant after its eastern wing broke away citing linguistic and ethnic discrimination to become the nation of Bangladesh.

On the other hand, unlike the dwindling of Pakistan’s minorities, India has seen the flourishing of its own, with Muslims going from less than 10% of the population after partition to more than 14% now.

India’s Muslims have seen all-round success too. They have held high office in political, judicial and military circles, and joined the ranks of the nation’s billionaires.

The autonomy that Kashmiris have aspired for is already built into the federal structure of the biggest democracy that humankind has ever seen. As a fully integrated part of it, whether now as a union territory or later once again as a state, it will be much better placed to deliver a better life to its people.

As India’s Ambassador to the UN, Syed Akbaruddin, so eloquently put it, the amendment of Article 370 has no external implications whatsoever.

The temporary security measures there have successfully prevented the engineering of violence and casualties; and as for dialogue with Pakistan, India remains committed to the Shimla agreement, which saw both nations conceive steps to normalise relations and end conflict.