Opinions

The next steps in Modi’s reform agenda for a ‘New India’

Author - Baijayant ‘Jay’ Panda

Posted on - 27 September 2019

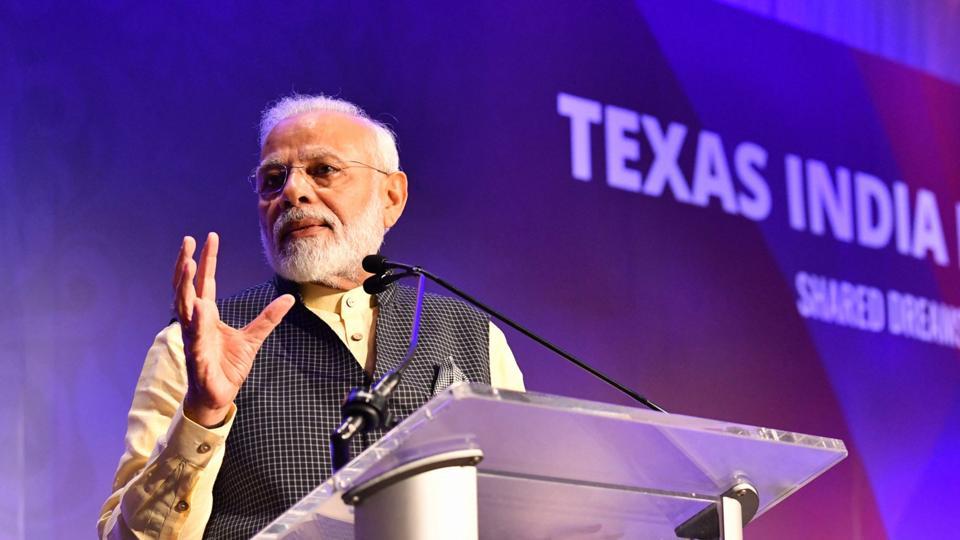

Image Source - Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Houston, US, September 22, 2019(PTI)

Downloadables

India has seen two significant inflection points this month. First, the dramatic simplification and slashing of corporate tax rates has finally, after several months of pessimism, led to a sharp turnaround in market sentiments. Second, the unprecedented extravaganza in Houston, United States, showcased Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s global stature, and India’s soft power, as never before.

Coming after the audacious legislative and constitutional amendments of the past three months, these have helped deepen the feeling that Modi is committed to creating a legacy of a radically revamped and re-energised Republic. There is no reason to believe that there will be any letdown in the breathtaking pace at which India has begun shedding old shibboleths now.

There are cobwebs aplenty from decades of waffling that need cleaning. Even on issues where a broad consensus had come about, either coalition politicsor the lack of political will got in the way. These included economic reforms, such as merging public sector banks into larger entities, and raising the caps on foreign direct investment in sectors such as insurance and aviation. Some of these have now been done away with the stroke of a pen.

There were also deep-rooted, fundamental changes that most parties had nominally agreed on, but also tacitly agreed to consider as unchangeable. Article 370 fell in that category. But its drastic pruning has laid to rest the idea that we must permanently reconcile to living with compromises that are explicitly at odds with the Constitution’s stated objectives.

The prime minister specifically emphasised this in Houston, saying that he was there to help break the defeatist attitude of “nothing can be done” about India’s long-running, intractable challenges. In that vein, the granddaddy of all “desirable but won’t happen in India” hurdles is one of the Constitution’s directive principles — a Uniform Civil Code (UCC).

The UCC debate has once again been sparked by the comments of a Supreme Court (SC) bench, while adjudicating a case from Goa, which does have a UCC. The SC is also scheduled to hear two petitions in November, which seek to jumpstart the process for drafting and bringing about a national UCC. If, as happened with triple talaq, the SC weighs in with a progressive judgment, the stage will then be set to bring about legislative changes.

Of course, there is no particular need for an SC judgment before the government goes in for such legislation, but it would require that much more effort and political capital. That too would be worth it, but needs to be considered in the light of the many other priorities that could be pushed through with the same effort.

There are scores of areas, if not hundreds, where reforms are needed. Even the less contentious ones could add significantly to India achieving its true potential. But the truly transformational ones require much more wherewithal, including the political will to legislate key constitutional amendments.

Judicial reform is one such. While the SC’s view on whether the time has come for a UCC will only start becoming clearer in November, its reservations about reforming itself are on the record. The SC’s scuttling of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) in 2015, after it had been passed unanimously by Parliament the previous year, was a major setback to unclogging the cumbersome, non-transparent collegium system of selecting high court and SC judges.

The NJAC had been modelled on the successful 2005 UK model. It provided checks and balances in the selection of judges, with representation from the government, inputs from the Opposition, and eminent members of the public, but with the higher judiciary continuing to hold the balance. Nevertheless, the SC overruled it in favour of continuing with the world’s only self-appointing judiciary.

One of the lesser-appreciated aspects of delaying judicial reforms is its enormous impact on the economy. Studies have long shown that the delays and uncertainties in the judicial system are costing us 2% in the GDP growth rate.

Now, the World Bank has specific information on how this is hurting the economy. In its Ease of Doing Business (EODB) index, Modi’s helmsmanship has seen India vault from ranking 142 among 190 countries to 77 in 2018. But when you break that down to the rankings’ sub-components, there are some stark contrasts. India’s gains have come from vast improvements in areas such as “construction permits” and “trading across borders,” reflecting both a more decisive government as well as the impact of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). But at the same time, a crucial component like “enforcing contracts” is dragging India down by lagging at a miserably low ranking of 163.

That is why judicial reforms are critical. Delay is compromising not just the economy’s ability to perform to its potential, but also the fundamental right of every citizen to speedy justice.

While awaiting the new Ease of Doing Business index rankings, out in a few days, it is worth recalling late Arun Jaitley’s contributions. As law minister in the AB Vajpayee government, he had introduced fast-track courts, with additional resources and rules limiting delays. Expanding these will help, but deeper reforms to expedite justice are needed.